Holika Dahan: Meaning, Rituals & Significance Before Holi

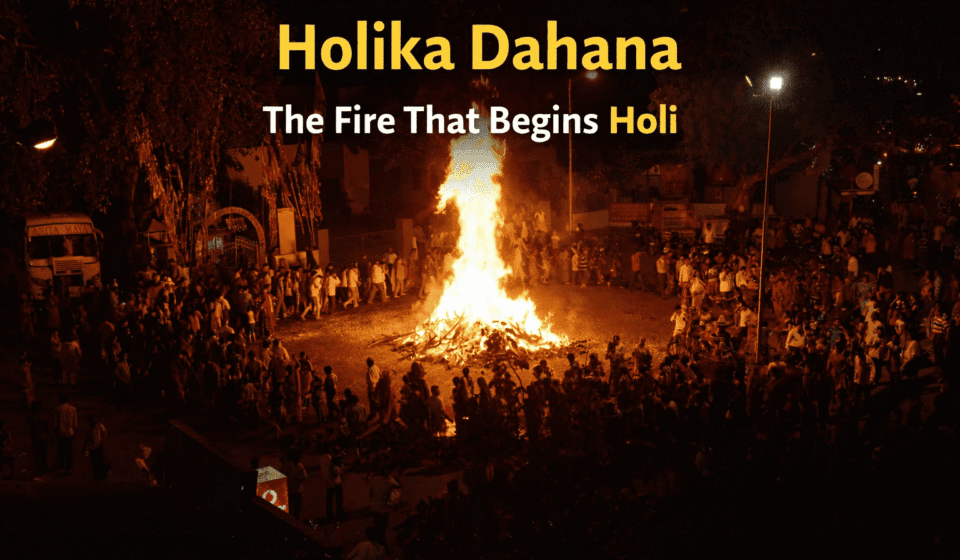

If you arrive in a North Indian town a day before Holi, you will notice something slowly taking shape in an open ground or at a street corner. A stack of wood. Dry branches. Cow dung cakes (upla) are placed carefully between them. It doesn’t look festive yet. It looks practical. Almost routine.

This pile is for Holika Dahan, the bonfire that takes place on the night before Holi. Unlike the following morning, there are no colours in the air and no music playing in the background. The atmosphere is steady and unhurried.

Holika Dahan Story: Why the Story of Prahlada Still Resonates

Most people grow up hearing the story of Prahlada, his father Hiranyakashipu, and his aunt Holika. It is often explained as the victory of faith over arrogance.

Hiranyakashipu was a powerful ruler who demanded to be worshipped as a god. His son Prahlada refused, choosing spiritual devotion instead. When punishments failed, Holika, who was believed to be immune to fire, sat with the boy in a pyre. She perished; he survived.

The story is repeated every year, but during Holika Dahan, it rarely feels like a dramatic lecture. It feels familiar. For many, the fire is a way of acknowledging imbalance, the idea that excess pride or anger eventually settles into ash.

In many places, you may notice a tall pole (the Manak) fixed in the ground before the wood starts piling up. This represents Prahlada and becomes the focal point of the ritual.

The Community Pyre: A Neighbourhood Ritual

Holika Dahan remains simple, and that simplicity is the reason it continues. In most places, the wood is collected collectively. It remains open to everyone, without tickets or private barriers.

Shopkeepers contribute crates, children gather sticks, and elders arrange the heavier logs. On the full moon night of Phalguna, families bring coconut, turmeric, flowers, and grains. As the flames rise, people walk around the fire, usually three or seven times, in a clockwise circle.

In agricultural regions, freshly harvested wheat or barley, called Hola, is roasted in the embers. These charred grains are shared as prasad, marking the readiness of the harvest.

If you join the circle, move clockwise. The pace is slow, and the moment often quiets the usual rush of the day.

The Seasonal Thaw: Marking the End of Winter

Holika Dahan occurs when winter is receding. In Northern India, winter evenings are often spent indoors. This gathering changes that rhythm.

Standing outside at night, around a shared fire, signals that the season is turning. The air is no longer sharply cold. Conversations stretch a little longer. The community begins to step outward again.

The ritual works at two levels: it marks a mythological memory, but it also marks a physical shift in climate and social energy.

Regional Variations: Same Fire, Different Expression

As you move across regions, the expression shifts slightly. In Braj, the connection to Krishna traditions is visible. In Rajasthan, public ceremonies may feel more formal. In Gujarat, the timing overlaps with financial transitions. In rural Madhya Pradesh, the agricultural meaning remains central.

Despite these differences, the structure remains consistent, a community gathering around a fire to mark a change.

The Balance: Why Fire Comes Before Colour

Holi morning is open, expressive, and unpredictable. But that energy only makes sense when you remember the previous night. Holika Dahan creates the pause; Holi fills it.

The fire reduces wood to ash. For many, it also marks a personal reset, letting go of small resentments or the heaviness of winter. The next day covers faces in a new colour. One is contained and reflective; the other is open and expressive. Together, they create balance within the festival.

Why It Still Matters

Even in high-rise apartments and growing cities, the ritual continues. Perhaps because it asks for very little. It does not require elaborate decoration or large expense; it only requires people to step outside and stand together.

Before colour spreads across the streets, there is a fire that brings people into a circle. And that circle is where Holi begins. The next morning, some people return to collect a small portion of ash (vibhuti) to apply on the forehead. It is considered protective for the new season.

Frequently Asked Questions About Holika Dahan

Q1. What is Holika Dahan, and why is it celebrated?

Holika Dahan is a bonfire ritual observed on the night before Holi. It symbolises the victory of faith and humility over arrogance, based on the story of Prahlada and Holika. The ritual also marks the seasonal transition from winter to spring and brings communities together in a shared space.

Q2. When is Holika Dahan celebrated in 2026?

In 2026, Holika Dahan will be observed on Tuesday, March 3, 2026, on the full moon night (Phalguna Purnima). The exact timing of the bonfire depends on the local Muhurat (auspicious timing) determined by regional Panchang calendars.

Q3. What is the story behind Holika Dahan?

Holika Dahan is linked to the story of Prahlada, his father Hiranyakashipu, and his aunt Holika. Hiranyakashipu demanded worship, but Prahlada remained devoted to Vishnu. Holika, believed to be immune to fire, sat in flames with Prahlada to harm him. She burned, while he survived. The story represents the eventual fall of arrogance and the endurance of faith.

Q4. What rituals are performed during Holika Dahan?

Communities gather around a prepared wood pyre on the night of Phalguna Purnima. Offerings such as coconut, turmeric, flowers, and grains are made. People perform parikrama (circling the fire), and in agricultural regions, freshly harvested wheat or barley (Hola) is roasted and shared as prasad.

Q5. What is the significance of collecting Holika Dahan ashes?

The morning after Holika Dahan, some people collect a small amount of ash (vibhuti) from the extinguished fire. It is traditionally applied to the forehead and is believed to offer protection and mark a symbolic fresh beginning for the new season.

Manisha Purohit

Manisha is a cultural writer at NativeSteps, focused on documenting India’s seasonal traditions, regional festivals, and sacred geographies. Her work centers on understanding the historical roots and lived realities behind rituals rather than simply describing them. Through careful observation and research, she contributes to NativeSteps’ mission of building a long-term archive of India’s cultural landscapes.