In India, time does not move in straight lines. It moves in circles. The year does not begin with a number on a calendar. It begins when the wind changes direction, when the sun shifts its path, when the first crop is cut, when the first monsoon cloud appears on the horizon. Indian festivals are how these changes become visible. They are not interruptions to routine. They are how routine learns to breathe.

To understand Indian festivals is not to memorise dates. It is to understand how India experiences seasons physically, socially, and spiritually. Indian festivals are not breaks from life; they are a part of it. They are how life is measured.

This page serves as an entry point into those moments when routine pauses, memory surfaces, and communities choose, again and again, to gather.

When the Sun Turns North, and the Harvest Comes Home

By January, the sharpness of winter begins to ease across much of India. The air is still cool, but sunlight lingers slightly longer. This shift, subtle but powerful, is marked by one of the most important solar transitions in the Indian calendar.

In mid-January, when the sun enters Capricorn, communities across the country observe Makar Sankranti. Skies fill with kites. In parts of North India, sesame sweets are prepared, warming foods suited to the season. The message is simple: the sun has begun its northward journey. Days will grow longer.

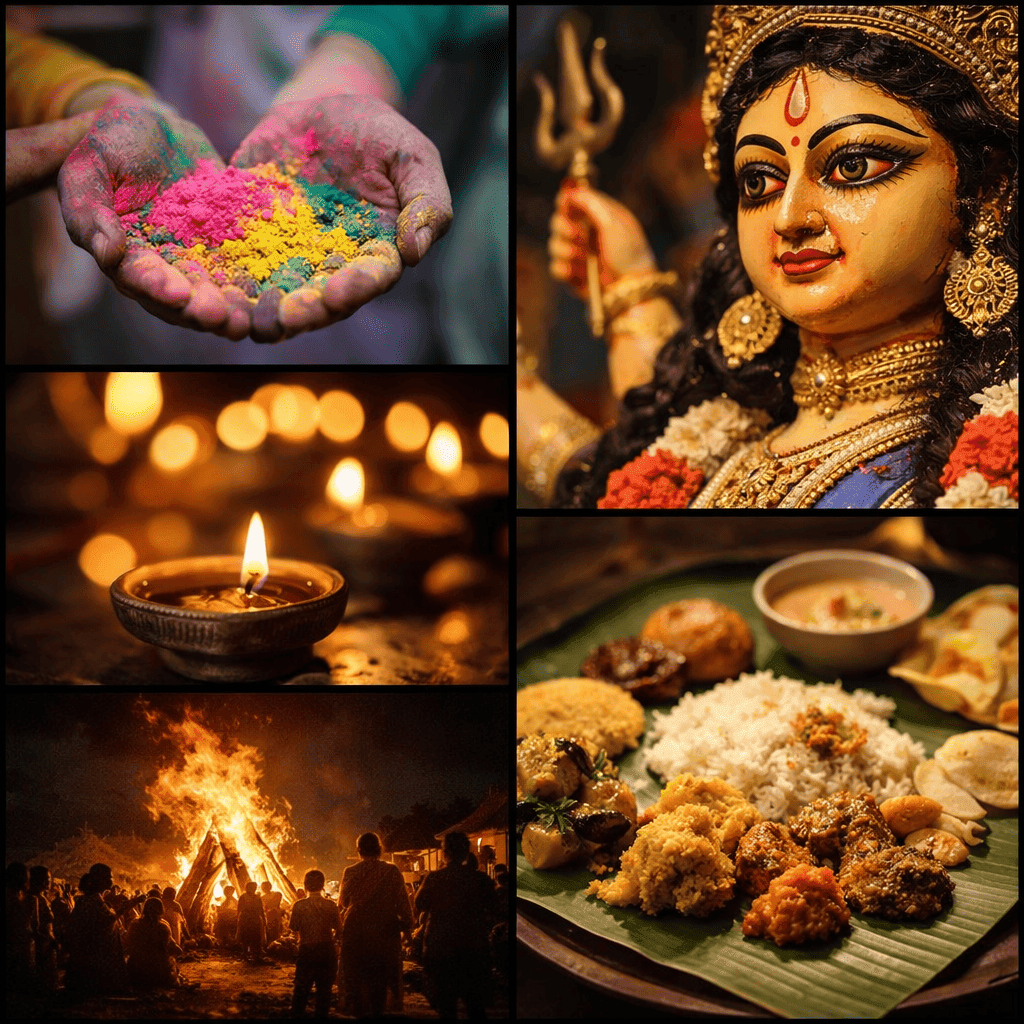

In Punjab, the evening before this transition glows with the bonfires of Lohri. Newly harvested crops are offered to flame. Songs circle fire because warmth is still necessary in January’s cold.

Further south, Tamil Nadu marks the same harvest cycle as Pongal, usually between January 14–17. Rice boils over deliberately in clay pots; abundance must overflow. Cattle are decorated, acknowledging their role in cultivation.

In Assam, fields give way to feasting during Bhogali Bihu. Temporary huts are built and then dismantled, symbolising completion.

These festivals share one truth: harvest has arrived. Effort has met the season.

The Last Stillness Before Spring

As February progresses, the landscape prepares for transition. The harvest is stored. The cold loosens its grip. Yet spring has not fully arrived. This in-between space is marked by Maha Shivratri, often falling in February or early March.

Unlike harvest celebrations, this festival belongs to the night. People fast. They stay awake. Temples remain open. It is a vigil more than a celebration. Seasonally, this makes sense. The earth is not yet blooming. The fields are resting. Maha Shivratri mirrors that pause. It becomes a spiritual bridge, a moment of internal alignment before outward colour returns.

India does not rush into spring. It prepares for it.

Spring: When Colour and New Beginnings Arrive

By March, mustard fields in North India turn yellow. Afternoons lengthen. Windows remain open longer. The body relaxes.

Spring first touches the land through Basant Panchami, usually in late February, but symbolically opens the door to spring. Yellow clothing mirrors blooming fields.

Soon after, in March, restraint dissolves more visibly during Holi. Colour is not decoration. It is released. Social hierarchies soften. Laughter replaces restraint. After winter’s inwardness, people return to one another.

A unique traditional festival, “Phool Dei”, is celebrated by kids in Uttarakhand. It says spring has come. In Spring, many regional New Year’s begin. Around March or April:

- Maharashtra raises symbolic flags during Gudi Padwa.

- Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka mark renewal through Ugadi.

- Kashmir welcomes its year through Navreh.

These festivals belong to spring because spring is a recalibration. Crops are replanted. Accounts are reopened. The year begins not in winter’s stillness, but in growing light.

Early Summer: Heat, Pilgrimage, and Reflection

As April deepens, heat intensifies across much of India. Rivers shrink. Dust rises. Travel becomes intentional. This is the season of pilgrimage.

In Uttarakhand, the sacred Char Dham shrines reopen around late April or May, aligning with accessible mountain passes. In Bodh Gaya and across Buddhist communities, Buddha Purnima usually falls in April or May, linking enlightenment with full moon clarity.

Jain communities observe Mahavir Jayanti in spring, emphasising restraint and ethical renewal, appropriate in a season when physical comfort is minimal.

Early summer festivals are less about celebration and more about discipline. Heat demands simplification. Ritual mirrors the environment.

Monsoon: When the Sky Decides

By July, clouds gather. The monsoon does not arrive quietly. It reorders everything. Roads flood. Fields soften. The sky becomes decisive.

In Uttarakhand’s hills, Harela marks agricultural beginnings through seed sowing indoors, practical and symbolic at once.

Early in the rains, domestic festivals like Teej appear, often centred around women’s gatherings and swings hung from trees heavy with rain. In August, Raksha Bandhan reinforces familial ties during a season when mobility is unpredictable.

As the monsoon stabilises, devotion expands outward. The birth of Krishna during Janmashtami arrives in August or early September, often observed at midnight, aligning cosmic timing with seasonal darkness.

Soon after, cities reshape themselves for Ganesh Chaturthi. Temporary installations rise and dissolve back into water, mirroring the monsoon’s own cycle of formation and release.

In Kerala, the rains bring Onam, typically in August or September. It celebrates harvest, homecoming, and memory. Its floral patterns reflect monsoon abundance.

Autumn: Clarity, Power, and Public Gathering

When the rains withdraw, the air sharpens. Skies clear. Fields mature. Autumn festivals are expansive because conditions allow gathering again. Across India, the nine nights of Navratri unfold between September and October. Dance, devotion, and discipline intertwine.

In West Bengal, Durga Puja transforms neighbourhoods into temporary cities of art. It culminates in Dussehra, when the imbalance is symbolically addressed.

In Himachal Pradesh, Kullu Dussehra extends beyond the national date, reflecting local continuity. In Telangana, Bathukamma celebrates seasonal flowers, rooted in local ecology.

Early Winter: Lamps Against Lengthening Nights

By late October and November, nights grow longer. The air cools again. This is when Diwali arrives. It does not assume light. It places it, one lamp at a time. Cleaning, settling accounts, and revisiting relationships all align with seasonal inwardness.

Around the same period, riverbanks glow during Chhath Puja, usually in October or November. Devotees stand in water at sunrise and sunset, directly engaging with the solar cycle.

Deep Winter: Reflection, Remembrance, and Community Warmth

As December settles in, introspection deepens. Sikh communities observe Gurpurab through collective prayer and langar, community meals that counter winter isolation.

Across cities and villages, Christmas brings midnight services and shared warmth. Islamic festivals such as Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha move through seasons due to the lunar calendar, reminding India that time is layered, solar, lunar, agricultural, and devotional.

Stories That Return Every Year

Indian festivals carry stories, but rarely in the way books do. These stories are remembered through action, lighting a fire, fasting for a day, or cooking a dish that only appears once a year. Children absorb them without instruction. Elders pass them on without formal teaching.

Over time, the story becomes inseparable from the ritual. Even when details blur, the emotion remains. This is how memory survives centuries.

The Same Festival, Seen Differently

No Indian festival belongs to only one place. The same celebration feels different in a village courtyard, a temple town, a mountain settlement, or a coastal city. Climate shapes it. Language shapes it. Local history reshapes it.

This variation is not an inconsistency; it is survival. Indian festivals endure because they allow people to make them their own, without breaking what they mean.

Food That Appears Only When the Season Calls It

Why These Festivals Continue

Indian festivals have lasted not because they are ancient, but because they are useful. They create pauses where none would exist. They bring people together without needing explanation. They help communities stay in rhythm with land, with memory, with each other.

Even when forms change, the need remains.

Festivals in a Changing World

Apartments replace courtyards. Messages replace visits. Firecrackers shrink into phone screens.

Yet the instinct survives. People still clean. Still cook. Still light lamps. Still gather, sometimes physically, sometimes emotionally. The form adapts; the impulse does not.

Indian festivals were never designed for a single era. That is why they move forward so easily.

A Living Calendar

Indian festivals are not preserved in the past. They arrive every year, altered slightly by the people who receive them. They ask for attention, not perfection. Participation, not expertise.

This page is only a beginning. Each festival opens into its own season, its own memory, its own way of slowing time, if only for a moment.

And then life continues, until the year turns again.